From Print to Built

Reflections on Practice, Pedagogy and the Formation of the Studio

This 2016 lecture at the AA explores the transition from large-scale practice to independent authorship, tracing how teaching, mixed-media enquiry, and process-driven design shaped a studio grounded in clarity, intent, and architectural precision.

In 2016, I was invited to give a public lecture at the Architectural Association as part of the Tutor Series, a programme that provided space for teachers to present their work beyond the unit context. The talk, titled From Print to Built, was an opportunity to reflect on the formation of my practice, PHASE3, and the ideas, methods, and processes that shaped the studio in its early years.

At the time, PHASE3 was still finding its public voice. The lecture traced the trajectory from my time working in high-end residential projects in New York to my years with Zaha Hadid Architects in London, where I worked on large, complex projects including the Stone Towers in Egypt, the Glasgow Museum of Transport, and the Dubai Opera House. Leaving Zaha’s office in 2013 was a pivotal moment. Stepping out of a globally recognised practice to form my own was both a professional risk and a personal necessity. I wanted to build a studio that reflected my own approach to design. I wanted to start applying something that was more personal to me and start creating an office that I believed in and started developing the kind of work that I wanted to push forward.

The talk focused on the three core components that made up the studio: the work of the office, the teaching and learning embedded in academia, and the buildings and products that the studio produced. I discussed how these elements fed one another, shaping a practice that did not view architecture as a closed system, but as a constellation of processes, tools, and cultural engagements.

Central to this early thinking was the belief that architecture could move seamlessly between different modes of making—buildings, objects, illustrations, and processes. I presented projects ranging from a residential building in Putney, to a large-scale masterplan in Kuwait, to interiors and product design, including swimwear and wallets derived from architectural facades. Rather than separating these activities, the lecture framed them as part of the same design methodology, each one informing the other.

I also spoke about the studio’s early commitment to process-based design and mixed-media production. At PHASE3, drawings, diagrams, prototypes, and moving images were not treated as presentation tools, but as integral parts of the design process. The practice was always thinking through making, producing physical tests, CNC-fabricated furniture, and laser-cut installations that reinforced spatial ideas at every scale.

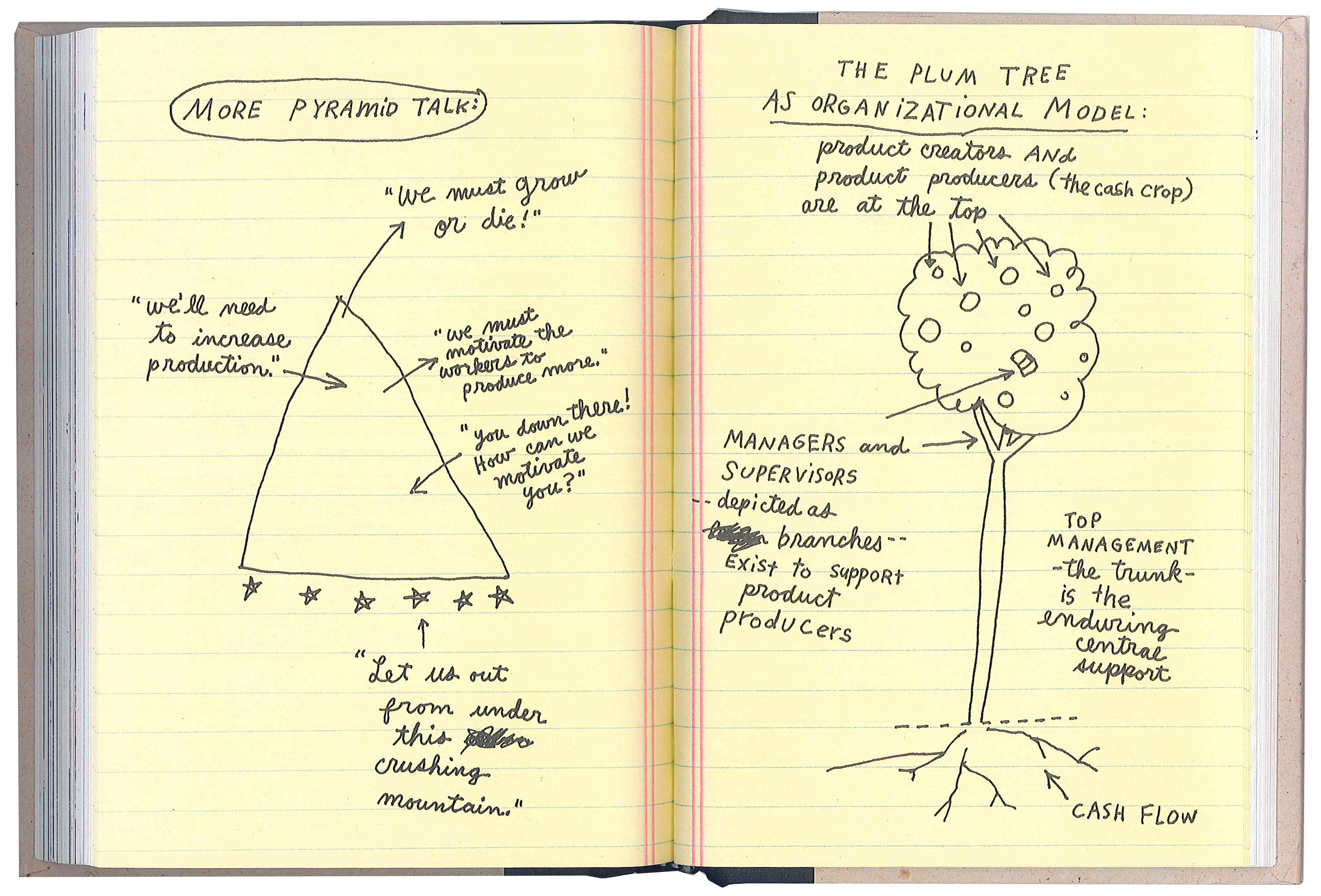

A key part of the lecture addressed the studio’s organisational structure, which I described using a visual metaphor adapted from Orbiting the Giant Hairball by Gordon MacKenzie. I rejected the typical corporate hierarchy in favour of a model that allowed creativity to grow through collaborative input, client engagement, and the evolution of the studio’s internal culture. Even in its earliest days, the studio was shaped to be a platform for others, not just a vehicle for my own authorship.

Throughout the talk, I reflected on the relationship between the academic and the professional. Teaching at the AA was not a parallel activity, it was a critical site of testing. The unit’s interests in illustration, multimedia, and process deeply influenced the studio’s design language, just as the work of the office shaped how I taught. There was no strict boundary between these worlds. Instead, they fed each other, producing an iterative exchange that sharpened both practice and pedagogy.

One of the more personal threads that ran through the lecture was the question of finding a distinct design voice after leaving a practice as visually strong as Zaha Hadid Architects. I acknowledged that, in some ways, I made a conscious effort to move away from that aesthetic lineage. I wanted to build something that was lighter, more playful, and driven by different formal and material interests. The Gate Mall project in Kuwait, one of the first I completed after leaving Zaha’s office, was intentionally filled with circular geometries, a quiet subversion of the formal constraints I had previously worked within.

The lecture also touched on the studio’s growing body of illustration work. Playful, diagrammatic prints and patterns that existed alongside the architectural projects. These graphics often emerged after the building process, as a way of reflecting on the work, reinterpreting spatial strategies, and testing compositional ideas beyond the constraints of site and programme. I discussed the importance of colour in this part of the practice. While colour appeared less directly in built work, it was fundamental in the studio’s visual language and post-project reflections.

"For me, I don't care what I'm designing, just as long as I'm designing something. Whether it's a building, a business card, or a wallet, it's about the design process and the thinking that drives it."

The final discussion circled back to the question of legacy and scale. I spoke openly about the challenges of starting a practice, navigating uncertainty, finding projects, building an office culture, but I also made clear that growth was not the primary ambition. I envisioned a studio of around twenty people, a scale that would allow meaningful work to develop without diluting design authorship. For me, that's the legacy, creating a space where people can develop over time and make their own projects, but somehow it still feeds into the office.

Looking back now, this lecture captured a formative point in the evolution of the studio. Much of what I spoke about then, the role of process, the importance of teaching, the interest in moving between scales, continues to structure the work of Tyen Masten Studio today. What has since evolved is the clarity of voice, the refinement of purpose, and a more deliberate alignment between architecture, cultural systems, and long-term relevance.